“Unapologetic: All Women, All Year” at Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (SMoCA) can now be enjoyed virtually, including listings, descriptions, and images of the artworks.

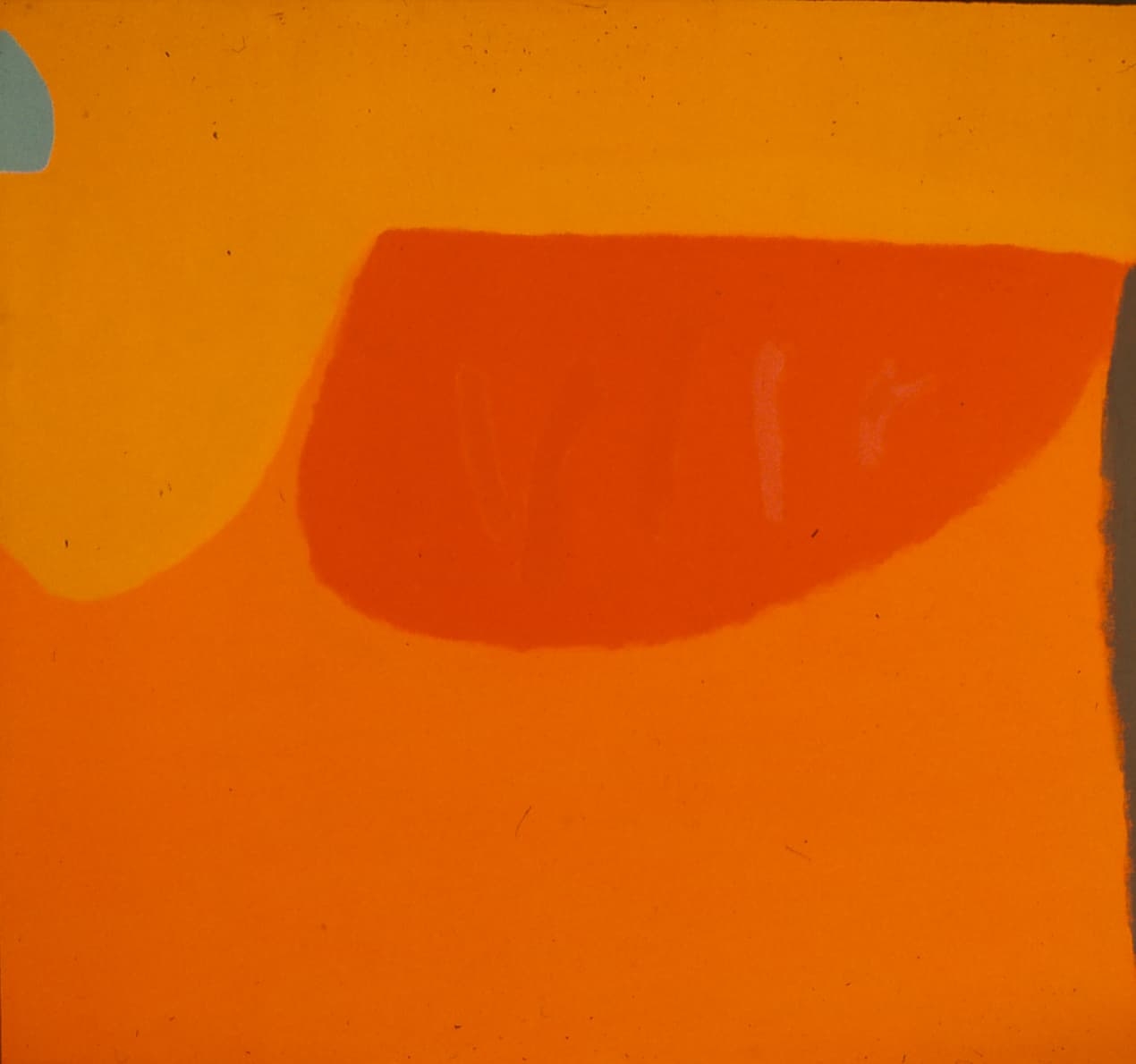

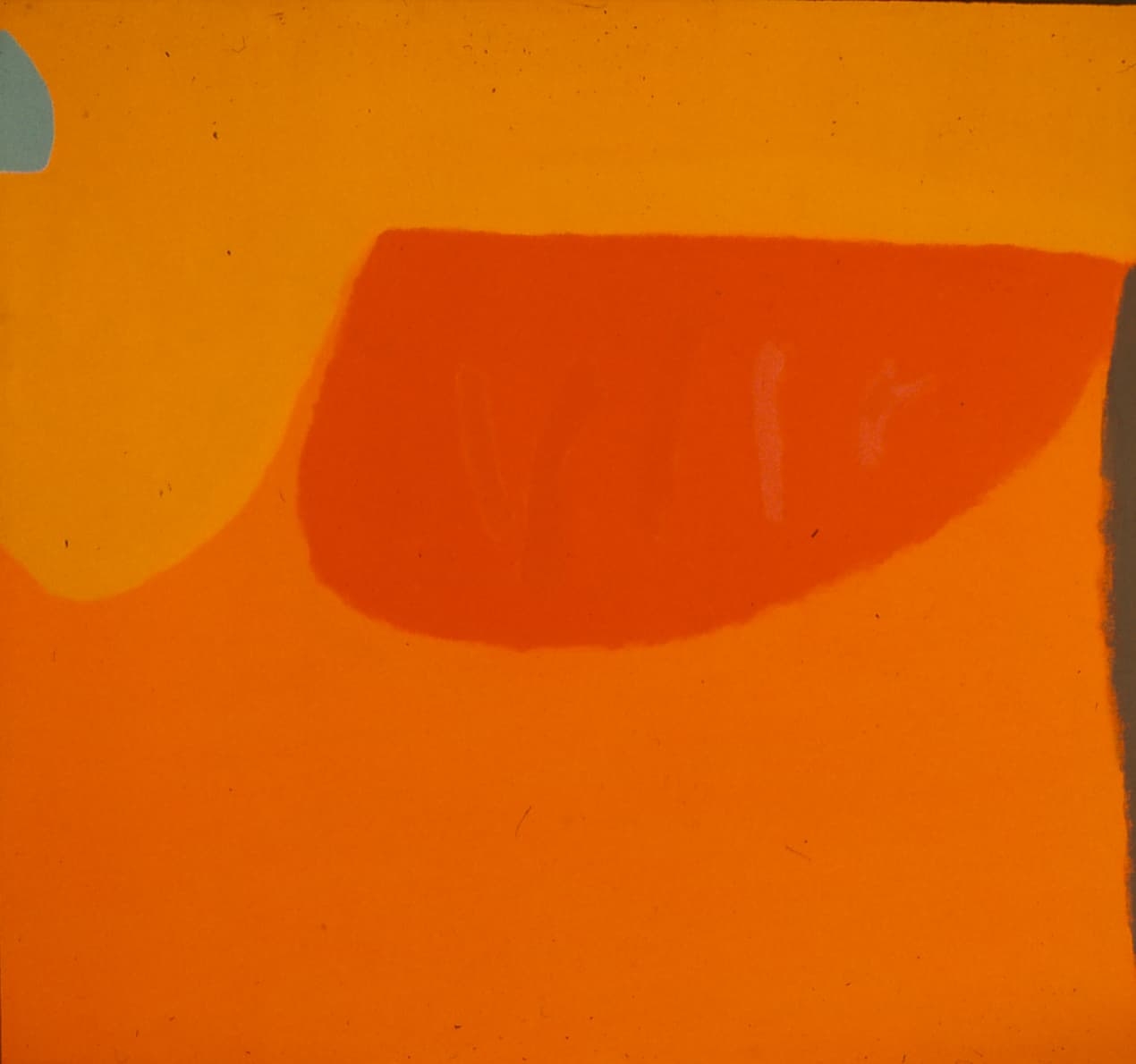

(Image above: Dorothy Fratt's Red Mesa, 1977. (Courtesy Scottsdale Fine Arts)

Celebrating the quality and diverse work of women artists, the exhibition opened Feb. 15, 2020 but has not been accessible since SMoCA closed March 16 in the city’s battle against COVID-19. The exhibition continues through Jan. 16, 2021.

“As we pivot and adapt to this temporary disruption, we are thrilled to bring one of our exhibitions online as a reminder of how important art is in all our lives,” says Jennifer McCabe, director and chief curator at SMoCA, 7374 E. Second St. “Now, more than ever, we can find inspiration and hope from the arts.”

Louise Nevelson, Lullaby for Jumbo, 1966. (Courtesy Scottsdale Fine Arts)The exhibition, comprising 35 40 woman artists worldwide, celebrates diversity. Materials include traditional wood, bronze, and innovative nylon cord and mediums such as modernist bronze sculpture, large abstract shaped canvases, conceptual art, written word, photography, printmaking, painting, sculpture, collage, and mixed-media installation art.

Louise Nevelson, Lullaby for Jumbo, 1966. (Courtesy Scottsdale Fine Arts)The exhibition, comprising 35 40 woman artists worldwide, celebrates diversity. Materials include traditional wood, bronze, and innovative nylon cord and mediums such as modernist bronze sculpture, large abstract shaped canvases, conceptual art, written word, photography, printmaking, painting, sculpture, collage, and mixed-media installation art.

Subject matter ranges from identity, connotations of beauty, abstraction, nature, domestic violence to war, politics, power dynamics, women’s rights/issues, and heritage. Racial diversity is recognized, too: Black, Native American, Latina, Middle Eastern, Asian, and White women artists are represented.

Lauren R. O’Connell, assistant curator, and Keshia Turley, curatorial assistant, selected the artworks from the collection of approximately 1,850 that the museum stewards for the city.

Women artists with Scottsdale connection

In particular, “Unapologetic” includes work by three artists who had or have a close connection to Scottsdale:

• Beth Ames Swartz (born 1936), a visual artist and long-time Paradise Valley resident;

• Her daughter, Julianne (born 1967), now living and working in upper New York State;

• Sculptor Louise Nevelson (1899–1988), who lived and worked at Cattle Track Arts Compound in Scottsdale during the 1970s; and

• Field color painter Dorothy Fratt (1923–2017), also a frequent Cattle Track guest, whose studio was in her home on the east side of Camelback Mountain.

Other Arizona-connected artists participating are Angella Ellsworth, Muriel Magenta, Adria Pecora, Sue Chenoweth, Laurie Lundquist, and Mayme Kratz, Phoenix; Barbara Penn, Cristina Cardenas, Bailey Doogan, Tucson, and Melanie Yazzie, Ganado.

“The exhibition looks to expand art historical discourse about female artists, who in the past have been overlooked due to their gender,” O’Connell says, referring to a recent study showing that only 15 percent of national art museum permanent collections are by women and even less women of color. “This number does not mean that there are fewer women artists but rather that institutions have prioritized collecting work by primarily Western male artists.”

These practices are beginning to change in these more equitable times, and SMoCA hopes “Unapologetic” will be a catalyst for greater inclusiveness.

“Most importantly, this exhibition is reflective of a broader conversation about what cultural spaces and institutions should aspire to be and encompass,” Turley explains. “Our spaces should reflect the diversity that is apparent in our own society, where individuals of all gender, race, sexuality, ability, and ethnicity — among many other differences — can feel a sense of connection and solidarity.”

Claudia Bernardi (born 1955), a participating Argentinian artist, says, “The title of this exhibition is so true to who we are as women... [T]he artists selected to be part of this exhibition share a professional life where we had to learn how to be assertive, clear-visioned, and ‘Unapologetic’ in order to continue creating the work we do and defending why we do it. Using the word ‘unapologetic’ to me comes from a place of strength; we aren’t looking to be combative, but we also aren’t asking for permission.”

Louise Nevelson and Dorothy Fratt

Windows to the West, Louise Nevelson, Scottsdale Mall. (Courtesy Scottsdale Public Arts)

Windows to the West, Louise Nevelson, Scottsdale Mall. (Courtesy Scottsdale Public Arts)

Nevelson, whose last exhibition at SMoCA was “[dis]functional: Products of Conceptual Design” in 2017, was assertive, clear-visioned, and unapologetic. One of the 20th-century’s most important sculptors, she is represented in the exhibition with her serigraph collage, “Lullaby for Jumbo” (1966), one of a dozen of her works in the SMoCA collection.

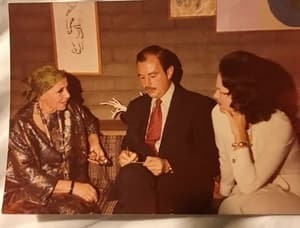

In the living room of the Dorothy Fratt and Bud Cooper home on Camelback Mountain, Louise Nevelson, left, chats with Cooper's niece, JoAnne Hutchison Cooper, left, and an art critic.Made with Including photographs of Nevelson’s assemblage sculptures, “Lullaby for Jumbo” has two layers: a black silkscreen of a complete sculpture on a yellow background and a black-and-white silkscreen of a sculpture cut into the shape of an opening cupboard. “The overlaying images create an abstract still life of her two-dimensional works, allowing the artist to push the boundaries of assemblage, collage, minimalism, and abstraction,” O’Connell explains.

In the living room of the Dorothy Fratt and Bud Cooper home on Camelback Mountain, Louise Nevelson, left, chats with Cooper's niece, JoAnne Hutchison Cooper, left, and an art critic.Made with Including photographs of Nevelson’s assemblage sculptures, “Lullaby for Jumbo” has two layers: a black silkscreen of a complete sculpture on a yellow background and a black-and-white silkscreen of a sculpture cut into the shape of an opening cupboard. “The overlaying images create an abstract still life of her two-dimensional works, allowing the artist to push the boundaries of assemblage, collage, minimalism, and abstraction,” O’Connell explains.

One of her many visits to Scottsdale was in 1973 to dedicate her COR-TEN steel “Windows to the West,” now beautifully patinaeing in the Civic Center Mall.

“Cattle Track people worked hard to get the piece in place and put together because one piece had fallen off on trip here,” recalls Janie Ellis, owner of the Cattle Track Arts Compound. Her parents, George and Rachael, homesteaded there in the early 1930s.

Nevelson, along with Philip Curtis (1907–2000), the great magic-realist painter and also a resident of Cattle Track after locating to the Valley in 1947, were preparing for some reveling in Scottsdale. He bought her a ten-gallon hat and cowgirl boots, Ellis recalls. She immediately put them on and asked, “Do you think Scottsdale is ready for me?”Fratt was ready for Phoenix when she and her first husband, Nicholas, and their four young sons moved to the desert from Washington, D.C., in 1958. There her father, Hugh Miller, had been chief photographer at “The Washington Post” for 36 years and president of the White House News Photographers Association.

She had started painting at 9, when her parents enrolled her in class drawing live nudes. At 15, she won first prize in the Corcoran Gallery Student Art Show.

“Mom was tired of the winters back East, and she wanted the open space and the beautiful light of Arizona,” says her son, Greg, who notes that she taught him to appreciate good art and identify bad art.

They rented a home in the Windsor neighborhood of north Phoenix and later, after her divorce, she purchased a home a block away, with the help of her parents. They built a studio in the back where she gave classes in color theory and painting. Future husband, Curtis ‘Bud’ Calvin Cooper, Jr., a rancher and farmer, was a student. The couple were also frequent guests at Cattle Track, where Fratt’s memorial service was held in 2017.

In the late 1960s, Cooper hired the celebrated Arizona architect, Paul Yeager, to design a home near Scottsdale on the east end of Camelback Mountain. Fratt helped with the design, including the stained glass windows. There they raised Greg and his young brother, Peter; the two older brothers had already moved out. As a wedding gift, Cooper asked Yaeger to design an art studio on the property; here she worked.

“It was in this home she entertained such notable art scene personalities as Howard and Jean Lipman, José and Geny Bermudez, and Louise Nevelson,” Greg says, noting that it was his mom who advocated for Nevelson to be the artist to complete what became “Windows on the West.”

Red Mesa by Dorothy Fratt (Courtesy Scottsdale Fine Arts)

Fratt’s single work for “Unapologetic” is the colorful “Red Mesa” (1977, acrylic on canvas), one of eight pieces the museum possesses of her work. Her last showing at SMoCA was in 2013. A member of the Scottsdale Fine Arts Council and 2000 recipient of the Arizona Governor’s Artist of the Year Award, she also has works in Arizona collections at the Phoenix Art Museum, the Tucson Museum of Art, and the Museum of Northern Arizona.

“Red Mesa” is a landmark in Apache County in northern Arizona.

Dorothy Fratt, circa 1970s. (Courtesy Greg Fratt)“Using color as an emotive language, Fratt worked in abstraction and color field painting to explore visual landscapes. Everything from a line to a

Dorothy Fratt, circa 1970s. (Courtesy Greg Fratt)“Using color as an emotive language, Fratt worked in abstraction and color field painting to explore visual landscapes. Everything from a line to a  Dorothy Fratt works in her Camelback Mountain studio in 1975. (Courtesy Greg Fratt)dot, no matter how small, was a channel for color and an opportunity for experimentation,” O’Connell says. She quotes art critic Harry Wood, who wrote of Fratt’s work, “Although the colors ignite each other with their brilliance, they seem to melt together, with the inevitability and ease of natural law.”

Dorothy Fratt works in her Camelback Mountain studio in 1975. (Courtesy Greg Fratt)dot, no matter how small, was a channel for color and an opportunity for experimentation,” O’Connell says. She quotes art critic Harry Wood, who wrote of Fratt’s work, “Although the colors ignite each other with their brilliance, they seem to melt together, with the inevitability and ease of natural law.”

“My mom was a colorist, and she drew from nature, whose forms inspired her, such as those in Navajo country, including ‘Red Mesa’ in the exhibition,” says Fratt, who lives in Louisiana.

He notes that her work is being shown simultaneously in three locations, at SMoCA; in the “Leap of Color” exhibition at Yares Art Gallery, New York City; and in the Paderborn Museum in the Westphalia area of Germany.

Fratt notes that art historians connect her to the Washington Color School with notable artists such as Kenneth Nolan and Morris Louis. However, “She did not want to be associated with a group,” he says.

“She was someone who stood up fearlessly for quality in art,” he adds. “She was her toughest critic. She didn’t paint to please anyone but herself; she painted to meet her own high standards.”

She wanted to be, and was, Dorothy Fratt.

Beth Ames Swartz

Beth Ames Swartz, Smoke Drawing No. 7, 1976.(Courtesy Scottsdale Fine Arts)Swartz came to the Valley one year later than Fratt, in 1959, with her husband, Melvin, who thought the Southwest was a good place to start a law practice.

Beth Ames Swartz, Smoke Drawing No. 7, 1976.(Courtesy Scottsdale Fine Arts)Swartz came to the Valley one year later than Fratt, in 1959, with her husband, Melvin, who thought the Southwest was a good place to start a law practice.

Born into a distinguished family, she was accepted into the fine arts program at the prestigious High School of Music and Art in New York City. She continued her art studies at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and New York University where she earned a master’s degree before moving to Arizona.

Beth Ames SwartzPainting and exhibiting while raising two children, Swartz was chosen to exhibit in many prestigious museum exhibitions early in her career, including the First Western States Biennial, which traveled to various sites including The National Museum of American Art in Washington, DC.

Beth Ames SwartzPainting and exhibiting while raising two children, Swartz was chosen to exhibit in many prestigious museum exhibitions early in her career, including the First Western States Biennial, which traveled to various sites including The National Museum of American Art in Washington, DC.

Years later, Swartz returned to New York, where she met her current husband, art dealer John D. Rothschild. In 1995, they returned to Arizona to stay and stayed. In 2002, The Phoenix Art Museum had a retrospective of her work, “Beth Ames Swartz: Reminders of Invisible Light.”

Her single work for “Unapologetic” is “Smoke Drawing No. 7” from 1976, created by passing a specially treated paper over a lit candle. These early smoke drawings –– she completed about 50 –– led to her later “Fireworks” series.

The exploration of fire led her to the great Jewish mystical work, the Kabbalah, she says. In 1976, she visited Israel and produced the “Israel Revisited” works, later shown at the Jewish Museum in New York and throughout the country in 1981–83, and her “Ten Sites” series, celebrating the lives of Biblical heroines such as Rachel and Rebekah.

Swartz has always worked in series. Her “A Moving Point of Balance,” for example, is a participatory environment with seven-foot paintings, music and color light baths; it was a 10-year project and traveled to nine museums nationwide.

This series is included in the 2017 AZPBS 29-minute documentary, “Beth Ames Swartz/Reminders of Invisible Light,” which will re-air nationally on PBS starting in May. Six catalogs and three books documenting her career and the documentary have been recently accepted in the prestigious archive at Getty Research Institute in California.

Her paintings document her journeys, actual and spiritual, to lands and locales, as well as philosophical, wisdom, and religious systems.

“I have always been committed to spiritual point of view, and I have found through my journeys that all life is sacred, and kindness and compassion are what we owe each other,” she says. For her life’s work, she received the 2001 Governor's Arts Award, the highest given by the state of Arizona.

Swartz says she wants to “translate philosophical concepts into aesthetic visual experiences.” And, the New York critic Donald Kuspit has called her a “postmodern spiritualist, using the variety of spiritual traditions to make a universal point.”

To assist others, she has hosted the Artists Breakfast Club at various locations in the Phoenix metropolitan area for almost two decades. The group connects artists, curators, and art professionals one to one and advocates for art in general. “It is the basis of my work, the basis of my life,” she says.

Swartz has always been driven to be the best artist she can be –– not the best woman artist. Still, she hopes “Unapologetic” will focus attention on the under appreciation and under representation of female artists in museums.

"These are exciting times to be a woman artist," she says. "Arizona-based artists, particularly women, have something unique to say, and I am honored to be included in this very important statement about bravery, courage, persistence, and talent.”

Click here to enjoy the exhibition.

By David M. Brown, a Valley-based writer (azwriter.com).